- This course has passed.

The Genius Of ….

28 September 2022 - 12 October 2022

10.45 – 12.45 Wednesdays

£66.00 – £165.00

Description

‘The Genius of . . .’ series explores the music of three great composers and reveals how they constructed their music, and, how in each case their music could never be mistaken for work by another composer.

“A most exhilarating experience to be guided along such a soul-searching journey by a lecturer possessing a great depth of knowledge.”

Course Outline

28 Sep 2022 – The Genius of GF Handel

Of the three musical giants born in 1685 – GF Handel, JS Bach, and D Scarlatti – Handel was the most cosmopolitan in terms of a personal musical style. In part, the reason for this lay in the experiences Handel gained through extensive travelling as a young man in Germany, and later through time spent in Rome, Naples, and Venice. The lecture begins by taking a close look at Handel’s life and career, and then goes on to plot the composer’s developing musical style. However, while Handel composed works in all of the important forms of the late Baroque, including sonata, concerto, and fugue, his primary interests lay in the writing of opera and oratorio and the lecture delves deeply into this repertoire to show Handel’s genius at work at its very best.

05 Oct 2022 – The Genius of Antonio Vivaldi

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) is arguably the one Baroque composer whose music is a direct reflection of the city in which it was composed: Venice. This, among other things, has much to do with: 1) Venice’s passion for spectacle and showmanship, mirrored so brilliantly in the fast movements of Vivaldi’s concertos; 2) Venice’s innate love of attractive melodies and adventurous harmonies, found, among other places, in Vivaldi’s choral music; and 3) Venice’s fascination with form, order and balance, which lies at the heart of all Vivaldi’s writing. The lecture explores Vivaldi’s genius for producing compositions that met the expectations of the various Venetian organisations that employed him, and presents a range of works – concertos, motets, oratorio – to illustrate this important aspect of his music.

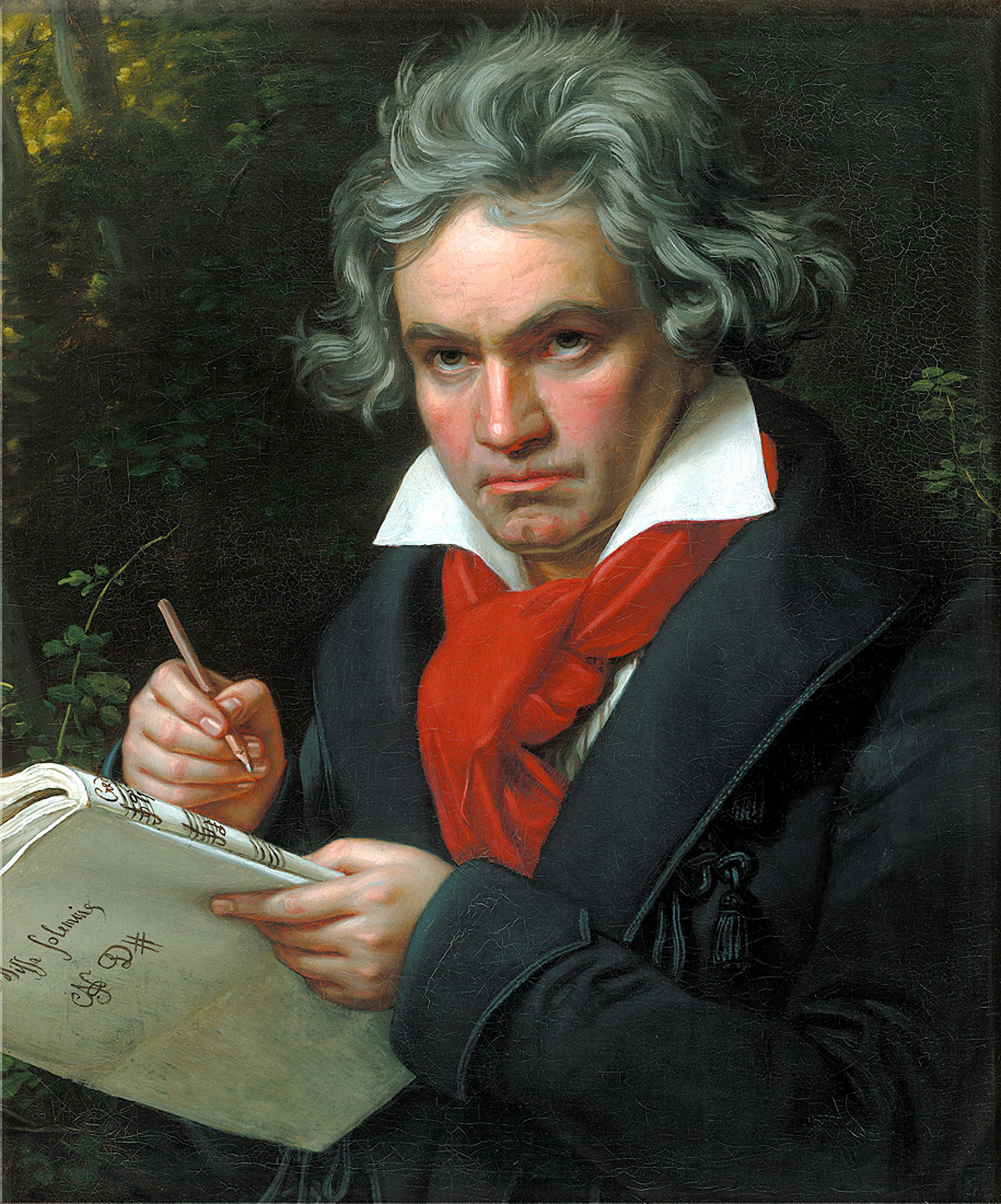

12 Oct 2022 – The Genius of Ludwig van Beethoven

Leonard Bernstein once observed ‘what makes Beethoven (1770-1827) great is his perfect sense of form – his ability to realise what the next note always had to be.’ Bernstein is correct in his assessment, since Beethoven projects a wonderful sense of self-assuredness in his music, giving the impression that the end product was inevitable. However, as Beethoven himself said ‘I carry my thoughts around with me for a long time . . . I change things, discard and try again until I am satisfied’, suggesting that like a craftsman, Beethoven often had to hone his ideas into shape until the right solution presented itself. Beginning with the Pathétique Sonata and chartering a course through the symphonies, the string quartets and the choral music, the lecture explores what it is that gives Beethoven’s music its unique sound.